This time, we decided to give a name to the possible root causes of what could be improved in our beloved country, Italy. We have decided to give them a fictitious name:

1. Technology transfer that doesn’t scale: The sin of inertia

Italian universities are among the oldest and most prestigious in Europe. They produce excellent research, yet they rarely produce venture-scale companies. The problem is structural.

Netval’s 2023 snapshot captures the gap clearly: public research institutions hold 8,882 patents in portfolio, but 1,241 active licensing agreements generated only €5.87M in revenues. And while there are 1,894 active research spin-offs, only 86 new spin-offs were created in 2023.

On the investment side, technology transfer is growing, but still not compounding. VeM reports 119 technology transfer investments for €223M in 2024: meaningful activity, yet still a relatively small slice of the overall VC engine.

This is a classic systemic sin: we reward motion over outcomes. Academic careers still prize publications, while technology transfer offices are often measured on volume rather than impact. The result is an ecosystem that stays busy, without consistently pursuing ambition at scale.

2. Talent retention trapped inside corporates: The sin of comfort

One of the ecosystem’s quietest vices is what doesn’t happen: experienced corporate leaders are rarely incentivized to leave and build startups.

If you’re a manager inside a large company and spot a real business opportunity, the default outcome is still to stay in place, because the incentives (salary, bonus, pension, safety net) overwhelmingly reward continuity over risk.

The numbers reflect the same dynamic. Italy’s startup dynamism is structurally weaker in areas where talent mobility matters most: in services, start-ups represent 15.5% of businesses vs 17% in the cross-country average. In manufacturing, Italy sits at 11%, below the UK’s 14%.

Corporates do engage but mostly through small external bets rather than founder-like leaps. Among the top 50 Italian companies, only 36% are active in startup investing and just 20% have a dedicated CVC fund. In 2024, 1 round in 4 included at least one corporate, yet the average ticket for corporate-led rounds is €364k (median €100k).

That’s the sin: comfort over contribution. Capital participates, but seasoned operators rarely step out and build.

3. A legal and bureaucratic infrastructure built for control: The sin of fear

Startups in Italy are still treated as exceptions to be supervised rather than assets to be enabled. Even basic corporate actions, cap table updates, share transfers, capital increases often translate into recurring administrative friction.

The numbers capture the baseline drag. In Doing Business 2020, Italy ranks 98th on “Starting a Business”: 7 procedures, 11 days, and a cost of 13.8% of income per capita (vs an OECD high-income average of 4.9 procedures and 9.2 days). And once a company is operating, complexity doesn’t disappear: enforcing a contract is estimated at 1,120 days in Italy, compared to 589.6 days in the OECD high-income average.

Regulatory uncertainty around labor, equity, and taxation adds another layer of hesitation precisely where speed matters most.

At the core sits fear of failure, and it’s more than personal psychology. On insolvency, Italy’s procedure is estimated at 1.8 years, with costs around 22% of the estate (vs 9.3% in the OECD high-income average), and a recovery rate of 65.6 cents on the dollar, below peers like France (74.8) and Germany (79.8). That combination discourages risk-taking and reinforces conservative behavior long before capital even enters the picture.

4. Seed and growth capital: a broken continuum: The sin of short-termism

Italy’s VC market shows a structural imbalance: seed capital exists, but growth capital largely doesn’t.

Early-stage activity has increased, but the pipeline narrows sharply beyond Series A. In 2024, Italy recorded 417 rounds for €1.5B, yet the system is overwhelmingly front-loaded: Pre-seed + Seed + Bridge accounted for 82% of all rounds, while only 21 rounds were Series B or later (5%).

That’s why rounds above €10–20M remain the exception, not the norm, and why the gap between early traction and true scale keeps repeating.

This is the venture sin of short-termism: we celebrate beginnings while neglecting endings. Startups are pushed to sell early or remain undercapitalized. Ecosystems that scale are those where capital intensity grows with ambition.

Zooming out, the pattern is consistent: Europe is near €60B while Italy is around €1.1B. Even at deal level, capital density remains thinner than major hubs.

5. Corporate M&A without a playbook: The sin of opportunism

Exits remain the weakest link in the Italian venture cycle.

We’ve seen this firsthand: startups priced at €3M and later acquired as an “emergency asset” at a fraction of that, not because the technology was worthless, but because the market lacked a structured path to a strategic outcome.

The macro picture is consistent: M&A volumes are still thin. In H1 2024, BeBeez tracks just 12 M&A transactions involving Italian-origin startups and scaleups (11 by Italian investors + 1 by foreign investors). For context, that compares with 15 deals in all of 2023 and 20 in 2022.

And when acquisitions happen, they often look defensive or opportunistic: acquiring talent or technology, rather than scaling a platform through repeatable integration. Without a playbook, this sin compounds upstream, founders build with fewer credible buyers in mind, and investors price risk accordingly.

6. Consulting disguised as venture capital: The sin of simulation

A more corrosive vice has quietly emerged: capital that looks like venture, but doesn’t behave like it.

Because the Italian pipeline is already front-loaded, “signal investing” becomes tempting. In 2024, Pre-seed + Seed + Bridge accounted for 82% of all rounds, while only 21 rounds reached Series B or later. That imbalance creates room for small tickets with limited follow-on: enough to claim involvement, not enough to carry risk when the company needs real fuel.

In practice, the simulation shows up in advisory-heavy structures and oversized “value-add” narratives: networking, visibility, boards. For founders, the hidden cost is time, focus, and cap table erosion, often with limited support when things get hard.

And when the journey from Series A to Series B stretches to a 31-month median, the difference between real venture and simulated venture becomes painfully obvious.

When venture becomes a service instead of a commitment, ambition shrinks, and trust erodes.

7. One dominant LP: the sin of dependence

Italy’s VC ecosystem remains heavily dependent on a single state-owned LP.

Public capital has been essential in building the market, but dependence comes with trade-offs. As of 31.12.2024, CDP Venture Capital-managed funds reported €4.309bn in assets managed (with €4.709bn committed across vehicles). CDP itself acknowledges that its resources “largely” come from the public sector, and it has set an explicit goal to catalyze €1bn of private savings and corporate capital under the 2024-2028 plan.

This shows up in the broader funding base: Italy’s LP pool remains highly domestic (68.5%) versus markets like Germany (43.8%). And Italian VC fund fundraising in 2024 stood at €837m, with no fund above €250m, a scale constraint that inevitably reinforces reliance on public anchors.

This final sin is systemic: when the ecosystem leans too heavily on one pillar, it slows when that pillar pauses. The challenge now is no longer activating public capital, but crowding in private LPs, without losing rigor and performance discipline.

From Diagnosis to Maturity

We like to think these seven “sins” are not accusations, but signals. They describe a system that has learned how to start, but is still learning how to scale and italians can tell themselves otherwise but data state otherwise. Suggestions? What’s next? Recipe? Maybe, but first of all acknowledge the status quo to then move into action mode. Yes actions, that is our wishes.

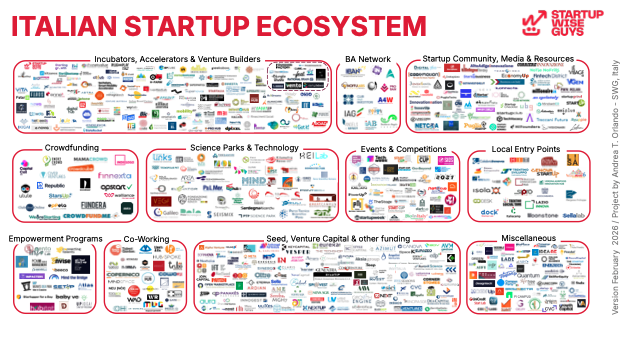

Below check out the latest 2026 Startup Ecosystem Map.

If you’d like to see the Italian Ecosystem map in high resolution, signup for our monthly newsletter.

Andrea T. Orlando, Davide Coppola

February 4, 2026